2022 September 29 News Article – Illinois Times + 60 other Illinois newspapers – Exonerating the Innocent. Opinion piece by Scott Reeder, former host of WGLT NPR podcast “Suspect Convictions”

Exonerating the innocent

Every once in a while, you meet someone who changes the trajectory of your life.

For me, that person was Darrel Parker, a gentle, kind man who worked in the Moline Parks Department.

Back in the early 1990s, I just had begun covering Moline City Hall and a friend told me that Parker was a convicted murderer who maintained his innocence.

I was only 25 and had never thought much about people serving time for crimes they didn’t commit. It was a different era, a time when people put much more faith in institutions.

Some folks have this misguided notion that newsrooms are full of bleeding heart liberals. In my 35 years in the news business, that has not been my experience. When I was a young reporter in Texas, my managing editor made news decisions based on the color of a crime victim’s skin.

When I worked as a police reporter in the Midwest, the night city editor was a man not prone to nuance. If someone was accused of a crime, they were automatically a “mope,” a slang term for an unsavory character.

Perched on his throne of white privilege, never was there an iota of doubt expressed that the person was guilty. We might as well have slapped the word “guilty” across the accused’s forehead.

But then I met Darrel Parker.

He was a lot like me: a white farm boy and an Iowa State graduate. He’d gone to prison when he was about the same age as I was at the time we met.

Parker suffered the tragedy of finding his wife murdered in 1955 and the misfortune of being interrogated a few days later by John E. Reid, a so-called expert in police interrogation. After more than 24 hours of coercion, Parker confessed to a crime he didn’t commit.

Even though he immediately recanted his confession, based on that confession alone, a jury convicted him. The confession made Reid famous. And what is now known as the Reid technique has become the standard form of suspect interviews for police departments across the country. It all started with a false confession.

Decades later, a serial killer on death row confessed to the murder. And a search of police files found that the killer’s car was parked in front of the Parker home the day of the murder. That and other information was never shared with the defense.

It took the state of Nebraska more then 60 years to acknowledge they made a mistake in Parker’s case and hand him a check for $500,000.

Parker, who died in February at age 90, never sued. He just asked the state of Nebraska to do the right thing. It would be easy to believe Parker’s case is an anomaly.

But I don’t believe that is the case. I’ve met too many factually innocent people who have done time.

This past week, Adnan Syed had his murder conviction thrown out by a Maryland judge. He became famous during the first season of the podcast “Serial.” His defense attorney was bad. Police didn’t pursue alternate suspects. And worse yet, they never informed the defense of the existence of these alternate suspects. An innocent man may have served more than 20 years in prison for a crime he never committed.

In 2016, I had never listened to a podcast. But when I was driving across Illinois with my wife, we decided to listen to “Serial.” About halfway through, I exclaimed, “This is really interesting, but I know a case that is even more interesting.”

Before the week was out, I was on the phone with Jay Pearce, the head of the NPR affiliate WVIK, and together with producer Lacy Scarmana, we produced a podcast that rose to No. 2 in the world on the iTunes charts.

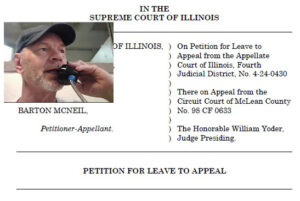

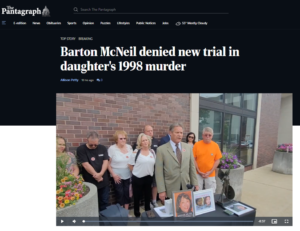

Subsequently, I investigated the case of Barton McNeil, a Bloomington man who was convicted of murder and is currently serving a life sentence. I believe he is innocent and was convicted based on faulty police work and poor legal representation.

I continue to work for his freedom. If you are interested in the case, listen to season two of the podcast “Suspect Convictions.”

In the dozens of wrongful convictions I’ve written about which have later been reversed, it’s rare to see a police officer disciplined even in cases involving perjury or incompetence.

Folks sometimes want to know why I ask tough questions of the police. Many work hard and do a good job. Others don’t. None are infallible.

I have met many victims of violent crimes whose cases were not vigorously pursued. Worse yet, I’ve looked into the eyes of too many people convicted of a crime they didn’t commit.

If journalists don’t hold those in power accountable, who will?

Scott Reeder, a staff writer for Illinois Times, can be reached at: sreeder@illinoistimes.com.