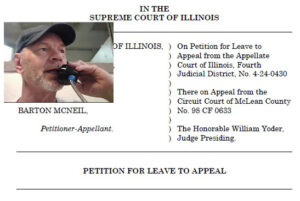

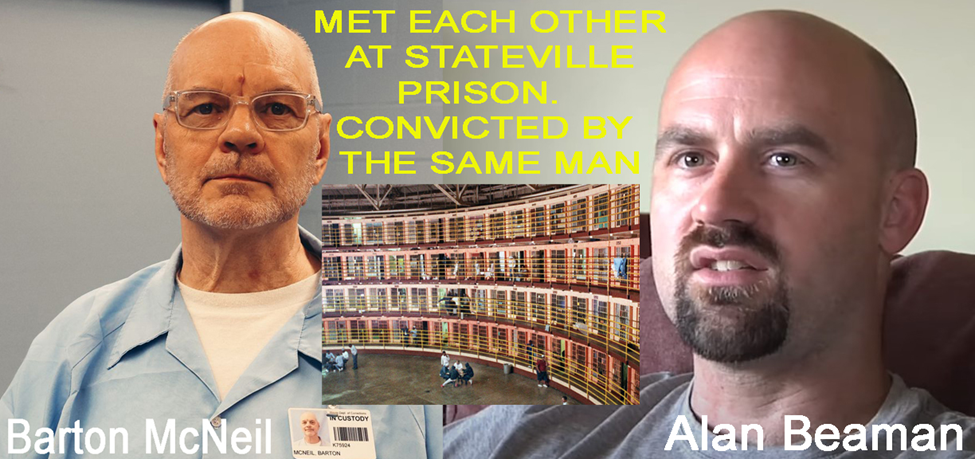

The Story of a chance encounter between Barton McNeil and now exonerated Alan Beaman, both wrongfully convicted in McLean County by Prosecutor Charles Reynard during the 1990s

April 8, 2024 | By Barton McNeil

Recently I learned of the $5.4 million settlement Alan Beaman agreed to accept from the town of Normal, Illinois, as a result of his wrongful conviction lawsuit in which he served 13 years. A mixed blessing to be sure, congratulations are due to Alan for his late-coming compensation for the many years he unjustly served behind bars while Jennifer Lockmiller’s true killer reveled in impunity.

At first seeming like a ton of money, minus the attorneys’ fees, Alan’s compensation amounts to a couple hundred thousand dollars for every year he spent mostly in an Illinois maximum security prison. How much is a year of one’s life worth?

It’s too bad no one involved in manufacturing Alan’s wrongful conviction was ultimately held to account, never mind the unaccountability granted to Lockmiller’s TRUE killer. While we’re all happy that this bitter chapter of Alan’s life has finally come to an end by wisely accepting the settlement offer, many of us wanted to see the civil case go to trial for a full outing of those who railroaded Alan into a wrongful conviction, if only to hold the authorities accountable by a public hearing of this cruel injustice.

Too little, long overdue, and absent any genuine accountability for those who maliciously rendered Alan’s wrongful conviction, we’re nonetheless pleased that he finally received some semblance of justice and can now get on with the rest of what remains of his life. Too bad that, like my daughter, Christina, Jennifer Lockmiller will suffer forever in death the injustice of her true killer’s getaway.

My own ongoing wrongful conviction now twice the length that Alan unjustly served in prison, followers of our twin McLean County wrongful convictions might be intrigued to learn of our personal connection.

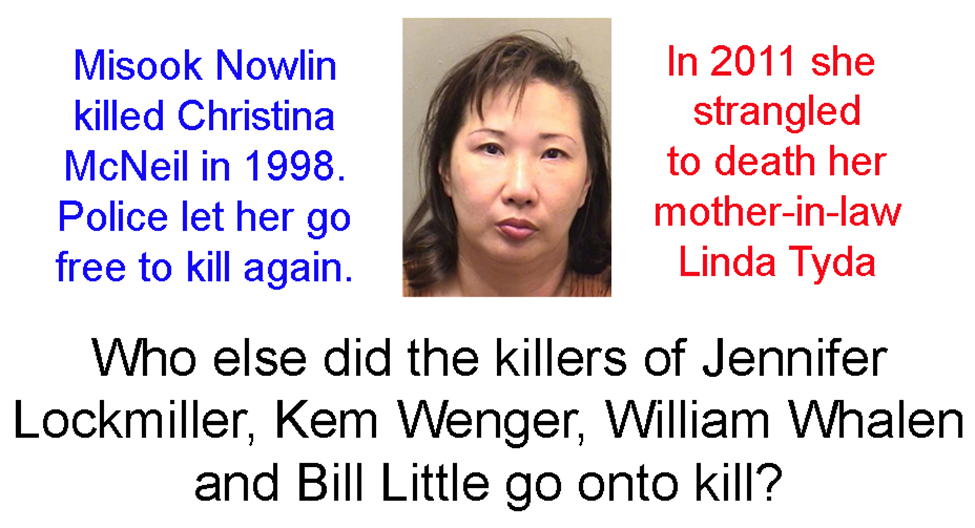

In the years leading up to Misook Nowlin’s 1998 killing of my daughter, Christina, to which Nowlin’s getaway my wrongful conviction served, I recalled hearing about the Jennifer Lockmiller murder and Alan Beaman’s trial, and news reports of several other recent McLean County murder trials too for that matter. Two of my coworkers personally knew Alan and remarked to me that he was surely innocent of the charges. While I didn’t follow these sorts of news events closely, my impression at the time was that meaningful evidence of his culpability was lacking.

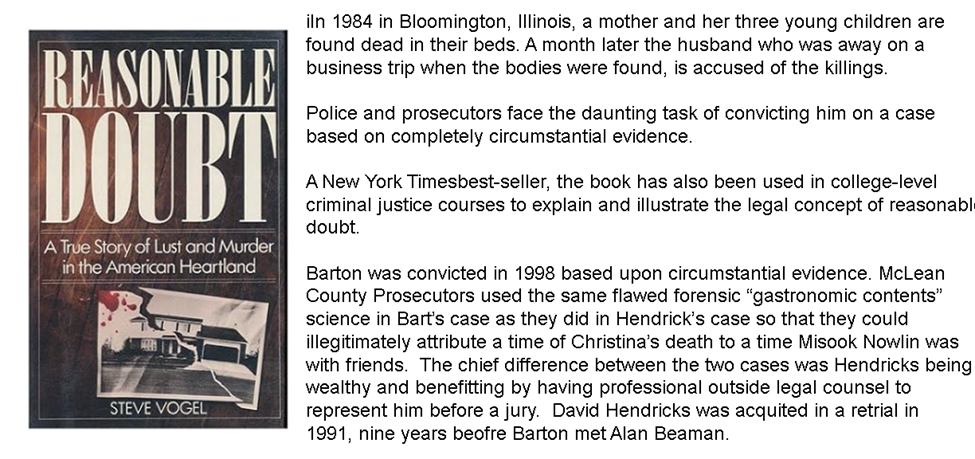

About a year into my prison sentence at Stateville maximum security prison, in October 2000 I went to the prison’s law library in search of legal materials related to the use of stomach content digestion rates as a supposed means of determining a timeframe of death—a “forensic specialty” that prosecutors used to falsely assign to Christina a timeframe of death in gross conflict with when I had last seen her alive (meant also to preclude Nowlin’s involvement in Christina’s killing). As such, I had firsthand knowledge of the fraudulent employment of this so-called “forensic science”, while prosecutors concealed from the investigative reports any tell-tale body temperature readings.

While researching the matter at Stateville that day I was taken aback to discover that the near-first use of this sort of forensic timeframe-of-death specialty was by McLean County prosecutors themselves in the Bloomington early-1980s Hendricks family massacre attributed to husband/father David Hendricks. Initially convicted but later acquitted of killing his entire family in a retrial, were David indeed innocent, the true killer(s) got clean away at David’s expense just as surely my child’s killer(s) centering on Nowlin got away at my expense—in both instances facilitated by the McLean County State’s Attorney’s Office.

Immediately coming upon Bloomington’s infamous Hendricks case as my timeframe-of-death research began—an eye-popping revelation all by itself—a more pivotal revelation was in store for me before the day ended.

While having photocopies made of the detailed Appellate Court ruling in the Hendricks case that day, I asked the inmate law library clerk if he could direct me to some materials regarding DNA testing, certain as I was that my child’s killer—Nowlin obviously—must have left her DNA presence on the newly laundered bedding on the night of the murder. In response, the clerk advised that I speak to the library’s janitor currently manning the vacuum cleaner who himself was similarly in pursuit of exculpatory DNA testing in his own case.

“Perhaps this guy has a line on some DNA-related information I can put to use”, I thought, wondering if any of the forensic circumstances of his case might happen to mirror my own. Often it is fellow inmates, indeed wrongful convictees, who are the best source of much-needed information regarding innocence advocacy and the appeals process when outside support and legal representation are absent.

As my conversation with the library janitor began with our mutual pursuit of DNA testing, he appeared smart enough to know the folly of seeking to test crime scene evidence were he the guilty party. Accordingly, his claim of innocence rang legitimate from the outset.

Inclined to give folks the benefit of the doubt, “If I can be wrongfully convicted with so little ado when Nowlin’s child-murder culpability was so transparently obvious, so too could ANYONE be the innocent victim of a wrongful conviction”, I reasoned.

When speaking to the details of is case the library janitor off-handedly remarked that he had been tried in McLean County.

“Holy crap!” I exclaimed, now wanting to know everything about his misfortune, desperate to find answers of how others’ fared at the hands of the McLean County State’s Attorney’s Office.

While in jail awaiting my one-sided trial, my once-reluctant suspicion became unshakable that prosecutors with the State’s Attorney’s Office knew perfectly well that Christina was the victim of a late-night intruder through her severely tampered-with ground floor bedroom window. More than just their awareness of my innocence, time and again police and prosecutors had gone to great lengths in what seemed like a concerted effort to conceal their knowledge of critical facts, circumstances, and evidence regarding Nowlin’s otherwise-obvious involvement in Christina’s killing.

Here now before me I had the opportunity to interview someone who may have also been a victim of prosecutorial injustice in my same county, of possible similar magnitude.

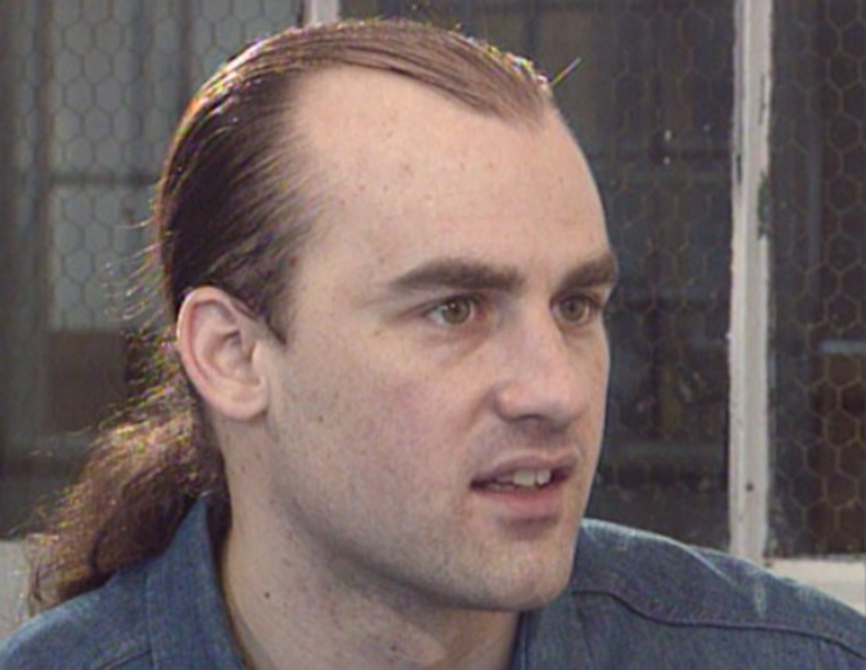

Alan Beaman

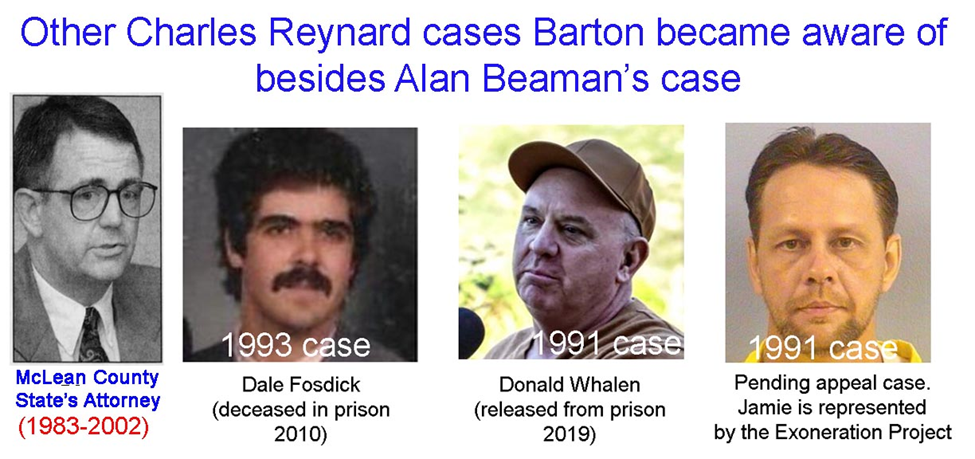

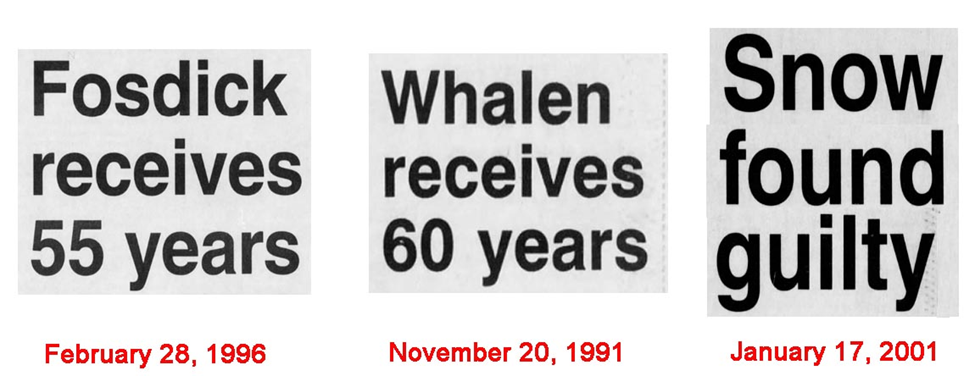

From local news reports the preceding decade—as in the case of the Lockmiller murder I had heard of the McLean County murder cases resulting in the convictions of Bloomington’s Donald Whalen, Dale Fosdick, and Jamie Snow. More recently I had read news reports to the effect that each of the above McLean County convictees were increasingly thought likely to be innocent.

While I had long assumed that my wrongful conviction was the exception rather than the rule (even in McLean County), I began to entertain the possibility that I was not the lone victim of a wrongful conviction produced by the county’s State’s Atorney’s Office after all. So infrequent were murder trials in the 1990s, were any more than just myself the victim of a wrongful conviction, that would be very difficult to explain away as unintended consequences of mistaken or even incompetent prosecutions conducted otherwise in good faith.

Yet, that the library janitor had been convicted in McLean County all by itself spoke to a probability of his innocence. Were any above three-or-more of us innocent victims of wrongful convictions, McLean County would have the highest wrongful conviction rate in the nation.

Riveted by the words of who also could be an innocent victim of the McLean County State’s Attorney’s Office, I continued my interview of the library’s inmate janitor by asking WHEN he’d gone to trial—a few years before me. I then asked WHO (which prosecutor) tried the case.

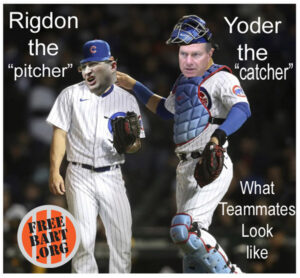

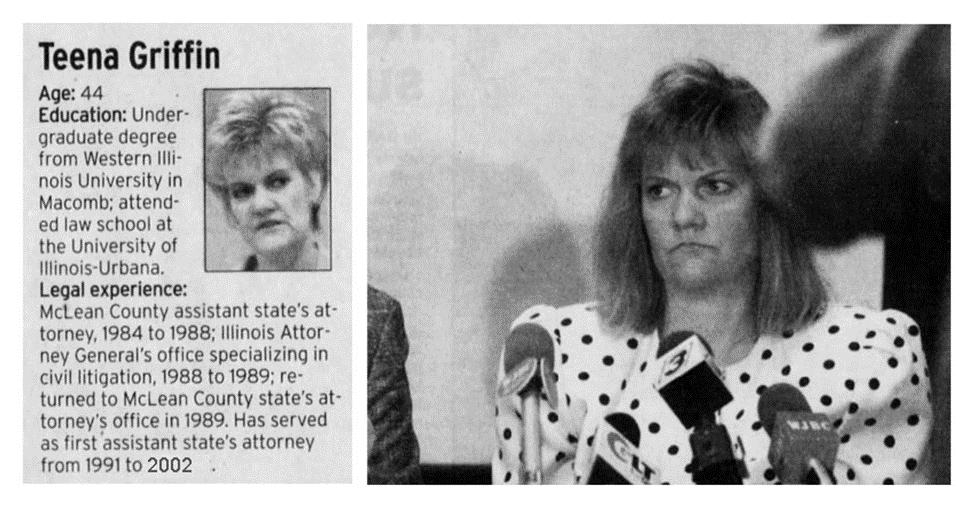

His genuine innocence as certain as tomorrow’s sunrise by his two-word answer: “Charles Reynard”—the decade-long State’s Attorney who tried the murder case himself (later to become a judge). Indeed, as then-State’s Attorney Reynard was the ringleader orchestrating my own wrongful conviction, his immediate like-minded underlings, Assistant State’s Attorneys Teena Griffin and Stephani Wong tasked with rendering my wrongful conviction in the service of Nowlin’s child-murder getaway—or how their Nowlin-friendly obsessions appeared at the time as I awaited trial—a stark characterization hardly unwarranted today.

Next, in the likelihood that I may have heard of this guy’s McLean County case before, in reply to my asking his name the library janitor identified himself as Alan Beaman himself, to which I immediately extended my hand in friendship. Obvious Alan had killed no one, my certainty of his innocence only strengthened as he spoke of the details of Reynard’s malicious railroading of him largely via fact-fabrication and evidence concealment.

As with the forensic fraud Reynard’s railroading cohorts employed to manufacture a phony Nowlin-friendly timeframe of Christina’s death that I had firsthand knowledge was a complete fabrication, so too was the very same stomach-content forensic methodology used to manufacture a narrow timeframe-of-death conforming to the State’s case against David Hendricks. More to the point, Alan Beaman’s own conviction rested entirely on the narrowest manufactured timeframe of Lockmiller’s death during which he plausibly “could have” had the opportunity to commit the murder—a window of time later proven to be TOOB narrow, rendering his culpability impossible.

Having just discovered someone else—Alan Beaman—wrongfully convicted during Reynard’s tenure as McLean County State’s Attorney—tried by Reynard himself—the clouds over Reynard’s production of my own wrongful conviction only darkened. Surely in a county with murder trials on the order of only one every year, Reynard couldn’t have (“mistakenly”) rendered two wrongful convictions in so short of a timespan.

Moreover, the likelihood that Bloomington’s Donald Whalen, Dale Fosdick, and/or Jamie Snow were also innocent victims of wrongful convictions produced by Reynard’s State’s Attorney’s Office skyrocketed after Alan shared with me his own experience at the cruel hands of Reynard—the implications of such an increasing probability too sinister to contemplate.

While Alan Beaman’s case involved detectives with the town of Normal, some of the very same detectives in neighboring Bloomington spanned the four above cases involving Whalen, Fosdick, Snow, and myself. Rendering Fosdick’s innocence more likely still, his case and mine were headed by the same Bloomington police detective, Larry Shepherd, the police authority who was most overt in providing Nowlin’s child-murder cover and effort to railroad me. In addition, as with Alan’s case, Reynard himself had personally tried Fosdick, which itself speaks to his likely innocence. The family of murder victim Pam Wenger were Fosdick’s fiercest defenders, who openly accused Reynard of outright framing Fosdick—mirroring Alan Beaman’s claims and his post-exoneration lawsuit similarly accusing Reynard of framing Alan, and of course mirroring what I maintained all along Reynard had done to me.

It’s one thing to say that a prosecutor was mistaken or even grossly incompetent. It’s quite another thing entirely for a collective of likely-wrongful convictees, who steadfastly maintained their innocence throughout, to say Reynard intentionally framed the innocent in the same manner that I was.

A testament to the innocence of Whalen and Snow, like me they were tried by Reynard’s immediate subordinate cohort, First Assistant State’s Attorney Teena Griffin who herself went to great lengths to undermine and outright conceal a litany of telling facts, circumstances, and evidence known to the Reynard/Griffin/Wong railroading trio in assurance of Nowlin’s obvious killing of Christina.

As I came to know Alan Beaman better in the months following our initial meeting, our twin wrongful convictions at the hands of Reynard’s office seemed to mirror each other in many ways.

Because I was moved to a different cellhouse and Alan transferred to a different prison entirely, our acquaintance was short lived. To the extent that I was able, I followed all the news reports regarding his intense long-running efforts to exonerate himself.

From my 2000 first meeting with Alan onwards, when the subject of wrongful convictions often arose in my letters to friends and family, I expressed certainty in his innocence. Not long afterwards my letters also posited an increasing likelihood that Alan and I were surely not the lone victims of whatever hidden agenda was driving Reynard’s production of wrongful convictions—Whalen, Fosdick, and Snow likely innocent victims of Reynard-rendered wrongful convictions also.

Some years later Alan had his wrongful conviction tossed and has since sought some compensation and accountability at the expense of those who unjustly took so much of his life. Like Christina’s murderer, thanks to Reynard Jennifer Lockmiller’s true murderer will never pay for her killing. For all anyone knows, just as Nowlin’s child-murder getaway resulted in her later 2011 killing of mother-in-law Linda Tyda, so too is likely Lockmiller’s murderer went on to kill again.

Later still the Exoneration Project managed to get Donald Whalen’s wrongful conviction reversed also, but only after he had already served the bulk of his sentence.

Later still, Jamie Snow became a client of the Exoneration Project—the effort to reverse his wrongful conviction ongoing.

So stringent the criteria and vetting process to become one of the exceptionally few to be afforded Project representation—the granting of such legal representation of Whalen (he now already exonerated), Snow, and myself speaks to our collective innocence all by itself, in addition to serving to indict the county’s State’s Attorney’s office as a chronic producer of wrongful convictions.

Had Dale Fosdick not died in fulfillment of the Reynard-rendered death-by-prison sentence, the claims of Pam Wenger’s family that he too was framed by Reynard for a murder that he was innocent of today could hardly be in doubt. If only because of McLean County’s astonishingly high wrongful conviction rate, Fosdick today also would surely have been embraced long ago by one of the innocence-advocacy projects in the absence of any meaningful evidence of his guilt.

Alan Beaman may not have recognized my innocence as readily as I recognized his when we first met in prison. After all, I had a unique perspective through which to view the manufacture of my own wrongful conviction. Unlike Alan and the other above likely victims of Reynard’s wrongful convictions, the identity of Christina’s true killer transparently obvious—the countless Nowlin-related facts and circumstances also known to police and prosecutors who dedicated themselves to undermining—assured that they too were every bit as aware as I was that Nowlin was behind my daughter’s murder. Such was my recognition of the wicked origins of Nowlin’s child-killer impunity handed to her by Reynard’s State’s Attorney’s Office on a silver platter, thus my recognition of the grossly unjust character of the Office as a whole likely to have victimized many innocents.

In contrast, Alan Beaman and the above fellow likely wrongful convictees had no idea who the true guilty culprits were in the murders they were being prosecuted for. Similarly, they had no reason to suspect that the authorities then railroading the into a wrongful conviction themselves had any idea who the true guilty parties were either.

Accordingly, plausibly able to dismiss the wrongful conviction efforts led by Reynard as a result of a mistake made in presumed-good faith or a consequence of incompetence, Alan and the above rest could not have recognized just how sinister Reynard’s efforts against them were. With no prospect of future accountability, Reynard might have produced wrongful convictions just because he could.

From where I sat behind bars, whatever grandiose theory I entertained in pursuit of a motive to explain why the McLean County state’s attorney had so overtly covered for Nowlin’s killing of my daughter, flew out the window upon my meeting Alan Beaman. In easy recognition that Alan too was the innocent victim of Reynard-produced injustice, our now-JOINT wrongful convictions had more fiendish origins than I had imagined under the assumption that mine was the rare exception. Now faced with the increasing prospect that the above other murder convictions were also of men as wholly innocent as Alan and myself, the insidious character of Reynard’s tenure as state’s attorney now had no limits.

Put another way, recognition of Alan’s obvious innocence only cast further darkness over whatever hidden agenda was behind Reynard’s wrongful prosecutions that, until then, I mistakenly presumed I alone to have been the rare victim of.

Thus remains the elephant in the room. What of those who actually DID commit the murders we were all wrongfully convicted of?

Obvious that Nowlin’s child-murder getaway directly led to her 2011 taking another innocent life in Linda Tyda—two if you include the ongoing unjust taking of my own life—and perhaps other Nowlin killings she may have gotten away with as easily as she got away with killing my daughter that we have no knowledge of, what can be said (or presumed) of those who DID kill Lockmiller whose prosecution of Alan abetted the getaway of? How likely is it that Lockmiller’s killer never went on to kill again?

Should we assume that the true killer(s) of Donald Whalen’s father then went about his life after getting away with murder, permanently free of accountability thanks to Reynard’s scapegoating of Donald, never to go on to kill someone else?

What about the true killer of William Little whose murder Jamie Snow is wrongfully convicted of? How many people has Little’s killer gone on to later murder?

Assuming that the above lot of Reynard’s convictees are all innocent and that the murders and associated true killers were unrelated to each other—then there have been at least four separate killers roaming the streets of the twin cities for three decades,—three since Nowlin’s 2011 arrest only for her latest murder of Linda Tyda.

And if the above murder cases were instead all related to each other other than by virtue of the true killer(s) impunity afforded by Reynard’s rendering of wrongful convictions following in their bloody wake, then perhaps the very same killer(s) were responsible for more than one of the murders that led to MULTIPLE Reynard-rendered wrongful convictions.

Either way, the implications to the safety of McLean County citizens are stark. In addition to Reynard himself taking the innocent lives of his wrongful conviction victims, his office endangered the Bloomimgton-Normal public, by intent or otherwise, by essentially granting free-reign-impunity to the true killers by railroading the innocent for those murders committed by others now roaming free.

At the end of the day, either it was four or more separate unrelated killers freely roaming our community for decades with no fear of prosecution, or else it was an outright serial killer or two on the loose enjoying the impunity afforded by Reynard’s production of convictions of innocent persons rather than of the killers themselves.

A pivotal event in my own wrongful conviction saga, my meeting Alan Beaman in prison and easy recognition of his innocence cast yet a darker cloud over what amounted to the orchestrated getaway of Christina’s obvious true killer to which Reynard’s wrongful conviction of me solely served. Suddenly faced with another innocent victim, in Alan, of Reynard’s wrongful conviction specialty that I naturally presumed I was the rare victim of—to say nothing of the increasing likelihood that Whalen, Snow, and perhaps other Reynard convictees were genuinely innocent too—the rendering of so many wrongful murder convictions to the benefit of genuine killers in a county with so few murder trials had to be by design.

Unable to account for Alan’s wrongful conviction as a mere mistake made in good faith or a result of prosecutorial incompetence, any more than I could account for my own wrongful conviction on such grounds, the many wrongful convictions produced by the McLean County State’s Attorney’s Office to which only true killers benefitted must have been in the service of an agenda unfathomable to us ordinary folks.

So ends the true story of my having met Alan Beaman in 2000 at Stateville prison on the bitter heels of the orchestrated getaway of Christina’s killer rendered principally by State’s Attorney Reynard, and the immensely stark (and dark) implications of my unexpected discovery that Alan too was a recent victim of a wrongful conviction also, to which Lockmiller’s killer, like Nowlin, so benefitted. – Bart

THE END